Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Student Manual

Table of Contents

Class #1 – Theme Returning to Wholeness. 10

Class #2 Theme- Perception. 14

Class #3 – Theme: Being Present. 17

Unpleasant Events Calendar. 19

Class #4 – Theme: Stress and Reaction. 21

Class #5 – Theme: Reacting vs. Responding. 23

Challenging Communication Calendar. 25

Class #6 – Theme: Skillful Communication. 26

Day of Mindfulness – Extended Session. 28

Class #7 – Theme: Taking Responsibility, Practicing Compassion. 30

Moments of Compassion Calendar. 31

Class #8 – Theme: Continuing the Practice. 33

Supplemental Reading Material 35

What is Mindfulness Practice?. 35

Opening & Closing and the Three Rings of Growth. 40

Meeting Difficult Moments with RAIN.. 42

The Science of Mindfulness. 44

The “Negativity Bias” of the Brain. 47

Unplug! (What do you feed your mind?). 56

Communication Lens 1: Passive, Aggressive, and Assertive. 58

Communication Lens 2: The Stoplight Model. 59

The Yellow Light: In-Between. 60

Styles of Distorted Thinking. 60

Awareness of Breathing: Stabilizing the Mind. 65

Noting, or Labeling, Understanding the Mind. 66

Loving-Kindness Meditation. 69

Nine Steps to Mindful Eating. 71

Maintaining a daily practice – a few suggestions. 85

Community Mindfulness Practice Groups. 88

MEDITATION GROUPS IN THE SILVERTON AREA.. 88

MEDITATION and Mindfulness Outside Salem and Online. 88

Useful Websites for Mindfulness Training. 88

Introduction

This manual provides an overview of what will be covered in each class of the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) course (along with resource material) that will be given to the staff of the Gather Psilocybin Community Service Center in Salem Oregon.

RECORDINGS

These classes are part of your teacher’s MBSR Teacher Training. Some of the classes may be video/audio recorded for educational purposes.

Orientation

- Welcome and teacher introduction

- Brief participant introductions

- Class logistics:

Gaining course access

- This course is taken via Zoom sessions.

- You will need a computer or smartphone with reliable internet access, a camera, and a microphone.

- A Zoom link for the course which will be provided via email by the teacher

- When it is time to attend a class click on the link or copy it to the internet address box and click enter and click on the join button.

Guidelines

- Learning from experience: How you benefit from this course is mostly dependent on your participation in class and in your homework. Try to set aside about 30 minutes each day for your formal practice. Perhaps you can find time first thing in the morning, during lunch, or prior to bedtime. Some people find that 30 minutes of meditation can be just as restful as sleep. Let finding time for practice be a gentle challenge and seek a realistic way.

- Be on time & respectful of the group process. We will cover a lot in our time together and you may miss something important if you are late. On the other hand, if you cannot avoid being late, please be sure to come in quietly anyway. It is better to be late than miss a session. If you will be absent or must leave early from a class, please notify the instructor beforehand.

- Confidentiality: Being in an environment where open sharing takes place can be stressful and may feel unsafe. In order for all members to feel safe in sharing their experiences, you are making a commitment not to discuss anything, including other’s reactions, with anyone outside of the group. What others say in group needs to stay in group. We will be on a “first name basis only” in group to help ensure confidentiality. The limits of my obligation to confidentiality are as follows: a) if there is a suspicion of child or elder abuse; b) if you threaten serious harm to yourself or someone else (this may be reported to the police or appropriate authorities); c) if a subpoena is presented for legal proceedings.

- Self-care and Choice: Dressing comfortably, eating lightly, having water available, having cushions, blankets, or benches available all may make your class experience a more enjoyable one. You always have a choice during any activities and can pass during any group activity or sharing periods. You always may choose to adjust what is suggested. For example, if I suggest closing your eyes, you may feel more comfortable or less threatened by leaving your eyes open and just not focusing on anything intently. You need to be able to reassure your nervous system you are safe!

- Be supportive, but do not try to fix others. Our intention is to create a safe environment. We support each other by simply listening and not offering advice nor trying to solve each other’s problems. The most transformative learning happens when we each arrive at our own realizations in our own time. While this is not a therapy group, it may be therapeutic. There may times when your sharing becomes personal or exposes vulnerability and we want you to know that this is a safe place for that sharing.

- One Speaker: A basic request that one person speak at a time instead of interrupting one another. Possibly leave some time for a breath before speaking to be sure a speaker has finished expressing their thought.

- Move Up, Move Back: During a period of group sharing, it’s encouraged that those who tend to speak a lot in a group listen more and that those who tend to speak less "move up" and take the risk of sharing more.

- Speak from Your Own Experience: Rather than intellectualizing or storytelling, it can be useful to encourage people to use "I” statements wherever possible, sharing what is true for them and not generalizing. A community can also agree that people don’t offer each other unsolicited advice.

- Be considerate in your sharing: Sharing a personal story about trauma can be a powerful experience, but we want to have people ask for permission first. Sometimes people will launch into triggering details of a traumatic event without first asking the group's permission, which can feel violating. Between people and in the group, participants can ask each other for permission to ask questions or share stories (e.g., "I appreciated what I heard you say in the debrief and have a story from my past that relates to yours. Would you like to hear it?").

- Session Recordings. These classes are part of your teacher’s MBSR Teacher Training. Some of the classes may be video/audio recorded for educational purposes.

- Getting to speak: During the dialog portion of each class you are encouraged to express your heartfelt thoughts and concerns. If you wish to speak, please either raise you physical hand or use the hand icon at the bottom of your screen.

- Communicate with Teacher. Please let the teacher know if you are having any difficulties. You may do so in the group or speak privately with the teacher. Time to talk before or after class, by email, or on the telephone will be available. If you have any questions or concerns that you wish to talk to the teacher in private, make your request known to the teacher via email, phone, of text so we may arrange to talk. To communicate with me: CompassionatePresence@yahoo.com or (971) 218-6641.

Please contact me directly to let me know if you’ll be late, have to miss a class or have other questions. Great topics for a private conversation include uncertainty about the practices, questions about resources, and any difficult or surprising conditions which arise during MBSR classes.

- Course Description

Intention: Through physical and mental exercises the intention of the course is to provide the experience and understanding of being mindful.

Dates, times, all day retreat: The course starts on June 11th and ends on August 6th. Each class, with the exception of class 7, will be held on Wednesdays for about 2 hours starting at 5:30 pm and end at about 7:30. The 7th class will be held on Saturday July 26th from 10 am until noon. The Day of Mindfulness will be on July 19th for about 4 ½ hours starting at 10 am and ending at about 2:30 pm.

See Compassionate Presence Mindful Community MBSR Student Manual on the CPMCOR.com website. This manual has course and class descriptions. Class themes:

- Class 1. Introduction to mindfulness

- Class 2. The role of perception in shaping our sense of reality.

- Class 3. The value of being present vs. doing

- Class 4. Stress and stress reactivity.

- Class 5. Responding to Stress.

- Class 6. Difficult or Challenging Communications

- Class 7. Incorporating what we are learning.

- Class 8. Keeping Mindfulness alive

Typical class format: Each class has a theme. During each class there will be a similar sequence of activities, with some variation.

- Introductions/check-in/thoughts and concerns about previous class

- Talk on current theme

- Still meditation

- Moving (walking) meditation

- Mindful movement

- Body Scan

- Dialog on thoughts, feelings, concerns, and comments on current class

- Homework assignment

- Closing

Brief Course Description

- Mindfulness: What it is & isn’t (what do you know?)

- History of MBSR: Mindfulness-based stress reduction - Wikipedia

- Research findings: See

- Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on Emotion Regulation in Social Anxiety Disorder - PMC,

- The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on the Psychological Functioning of Healthcare Professionals: a Systematic Review - PMC

- Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on Mental Health and Psychological Quality of Life among University Students: A GRADE-Assessed Systematic Review - PMCE

- Risks & benefits

NIHNiHJun2021.pdf (NIH News In Health June 2021, Mindfulness for Your Health The Benefits of Living Moment by Moment)

Sensing emotions in your body involves recognizing physical sensations that correspond to emotional states. This awareness can enhance emotional intelligence and well-being.

Physical Sensations and Emotions

- Tension: Often felt in the shoulders, neck, or jaw during stress or anxiety.

- Butterflies: A fluttering sensation in the stomach can indicate nervousness or excitement.

- Heat: Flushing or warmth in the face may accompany embarrassment or anger.

- Heavy limbs: A feeling of heaviness can signal sadness or fatigue.

Mind-Body Connection

- Emotions manifest physically due to the body's response to stressors, often linked to the autonomic nervous system.

- Techniques like mindfulness and body scanning can help individuals identify and interpret these sensations.

Practices for Awareness

- Mindfulness Meditation: Focus on breath and bodily sensations to enhance awareness of emotional states.

- Journaling: Writing about feelings can help connect emotions with physical sensations.

- Body Scan: A practice where individuals mentally check in with different body parts to identify tension or discomfort.

Benefits of Sensing Emotions

- Improved emotional regulation and resilience.

- Enhanced communication of feelings to others.

- Greater overall mental health and well-being.

Understanding these connections can lead to better emotional management and personal insight.

Read:

Somatic Feelings: Identifying and Managing Emotions in the Body

Emotional Body Chart: Map Your Feelings and Find Balance

How to Express Your Feelings: 5 Emotions to Understand

- Intro to still meditation

- Questions, comments, or concerns about the orientation?

REMINDER: to bring raisin or other small piece of fruit or vegetable next week

Close

Class #1 – Theme: Introduction to Mindfulness

We start our journey together with our attitude and feeling towards our life. We suggest that there is much more right with you than there is wrong. No matter what the problems and challenges they can be worked with. This course is an opportunity to do just that in a supportive environment.

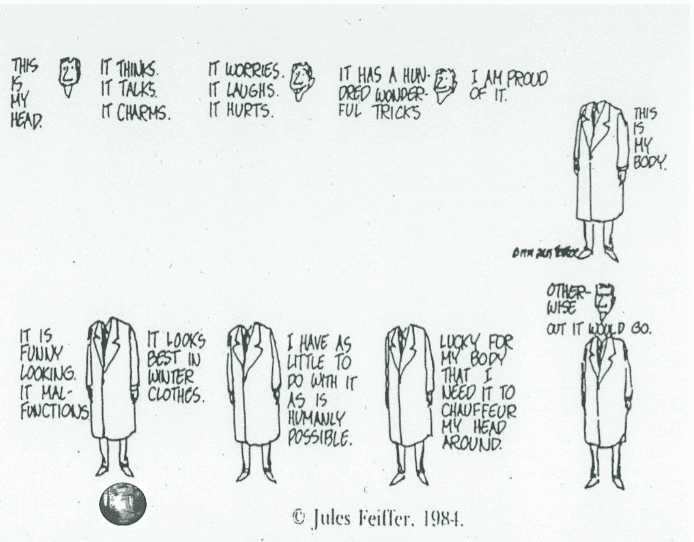

Learning about mindfulness is an embodied, experiential process. So often we treat the body as a machine the mind is driving around. We separate our body from our mind in a fundamental way and in doing so, we miss many cues about stress and reactivity which manifest in the body. And we miss some possible roads towards healing, stability, and stress reduction. A disconnection from the body may be a part of our strategy for “pushing forward” to a goal but instead results in an accumulation of stress. Mindfulness, then, is a journey of discovery with our self as both the one taking the journey and the one being explored.

Our first job in mindfulness is to return to feeling the body more fully. To this end, we utilize both formal and informal components of mindfulness practice.

Formal practices are those for which we set aside a chunk of time. The Body Scan is a very simple but not easy to do formal component which guides us toward improved body awareness. Some of the other formal practices we will explore in the course include Awareness of Breathing Meditation, Listening Meditation, Open Awareness Meditation, and Mindful Movement. All of these components are meant to help us experience the moment and not get caught up in the story behind the experience.

The informal component is taking time during the day to return to feelings in the body. We can start this process of discovery by scanning our body while holding questions such as: How am I? What sensations am I experiencing in the body? What is the emotional tone? What are the dominant thoughts arising right now, at this present moment?

Class Activity List

- Welcome, greeting, logistics

- Opening practice

- Mindfulness definition review

- Group discussion: Review Grounding Guidelines, previous session, and mindfulness challenges and issues

- Raisin meditation

- Brief Mindful Movement

- Body scan-abdominal breathing

- Discussion on Movement, Raisin Mediation, Body Scan

- Home practice assignment

- Closing practice

Home practice:

- Consider: how will you make time for home practice? What's a realistic challenge?

- Formal: Body Scan 3 to 6 days this week possibly using any or all of the 15-minute recording provided. Shorter and longer versions are available on the website & Insight Timer.

- Formal: Eat at least one meal mindfully (suggestions under Nine Steps to Mindful Eating and think back to how you ate your raisin).

- Informal: practice the "mindful check-in" during the day. Noting physical sensations, emotions, and thoughts. Dropping below the story line to the felt sense of what's happening.

- Try the Nine Dots Exercise (next page)

Supplemental: Note about supplemental materials: if you have a choice between reading about practice and doing practice, you know what to do!

- Read What Is Mindfulness Practice by Tim Burnett

- If curious about the science of meditation, read a summary of findings under The Science of Mindfulness.

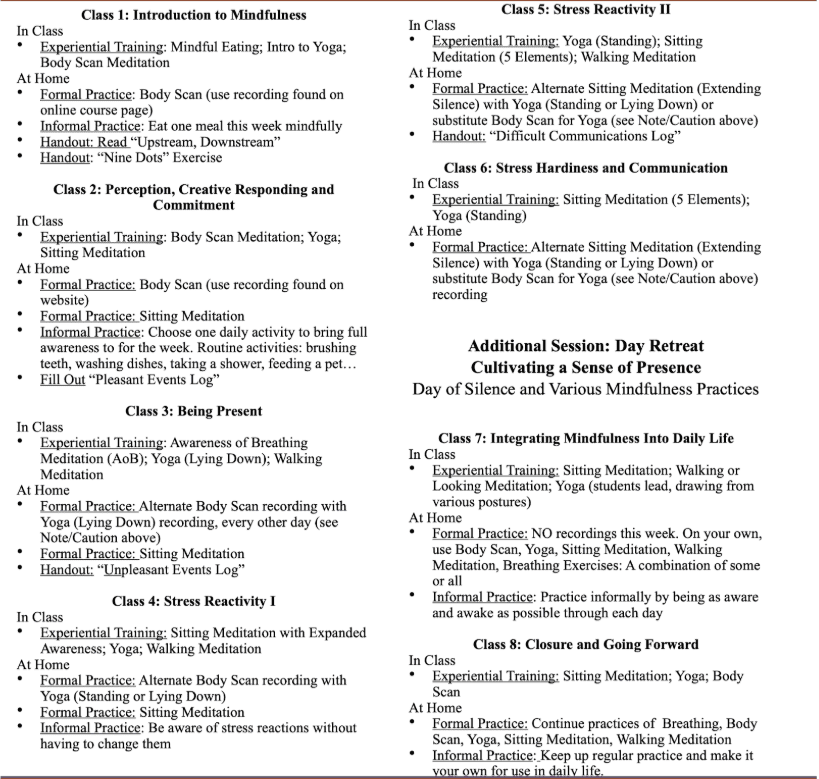

Nine Dots Exercise

Connect up all these dots with four straight lines without lifting the pencil, and without retracing prior lines.

Mindfulness Defined

“Mindfulness is paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.”

- Jon Kabat-Zinn

“Mindfulness is the awareness that arises out of intentionally paying attention in an open, kind, and discerning way.”

- Shauna Shapiro & Linda Carlson

Three keys to mindfulness:

- Intention – choosing to be more deliberate in how we use our mind

- Attention – knowing where the attention goes, bringing it to the present

- Attitude – accepting that what is here, is here.

Class #2 Theme- Perception

Our minds are powerful filters. From the broad range of our sensory experience (5 senses, plus our mind) we are consciously aware of only a slice of this full reality. And our minds are also powerful constructors. From the glimpses of reality perceived an entire universe is constructed. Consider perception in light of your daily experience and findings from psychology. How do processes like what you pay attention to and your mood and attitude affect what you perceive?

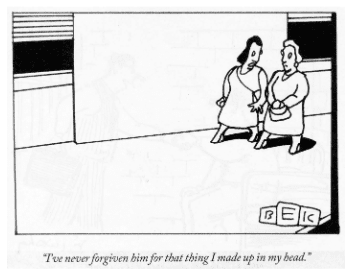

Through mindfulness we can become more aware of both what we are noticing as we see the “spotlight of attention” moving around the “theater,” and we can also start to be aware of the darkness around the edges of that spotlight. What are we not noticing? Are our conclusions about ourselves and others really accurate? These are usually based on partial data.

Consider how attitudes, coping strategies and habits affect your response to the stressors in your life. What have you learned in your mindfulness practice about these tendencies and the possibilities for responding in different ways?

Looking at our efforts to perceive reality in a different way let’s think of this effort just as you would one of your sense organs such as your ears and eyes. To make sure your sense organs are functioning as they should, you probably get them checked on a regular basis. You may see your ophthalmologist, dentist, audiologist and other medical professionals regularly to check up on your sense organs. My question to you is “How often do you get your perception ‘lenses’ checked”? After years of being influenced by social and cultural influence, by family and life experiences, wouldn’t you think your perception lenses need to be adjusted to make sure you’re perceiving life correctly?

Fortunately, in most cases, this examination and the related adjustment/treatment aren’t painful. There’s no shot of Novocain. No drops that dilate your perceptions. There may be some downsides to the process of adjusting/treating your perceptions though. First, both the examination and the treatment may take some time (i.e., the rest of your life) and second, restoring clarity to your perceptions may have jarring side effects. You may say to yourself, “How could I think that?” or “Wow! Was my thinking off-base or what!”

If this perception adjustment, this getting rid of distorted perceptions, provides such wonderful results, aren’t you anxious to find where the nearest treatment center is that may help people get rid of distorted perceptions. For the sake of brevity, I’m going to call such a person a perceptologist[1]? It turns out there’s one real close by… in your consciousness. You see, all you need to do[2] is apply a solution of mindfulness to your perceptions on a regular basis. It may do wonders!

As part of the home practice consider a difficult situation that has arisen, recently or in the past. How did your reactions and perceptions affect this?

Class Activity List

- Welcome, greeting, logistics

- Review previous material

- Opening still meditation

- Didactic on Perceptions and distortion of reality

- Introduction to Walking meditation

- Guided body scan

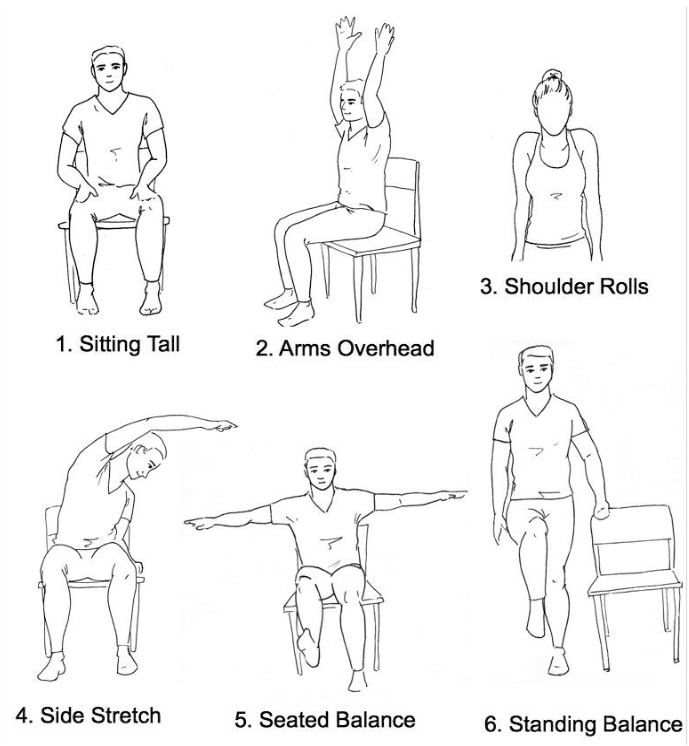

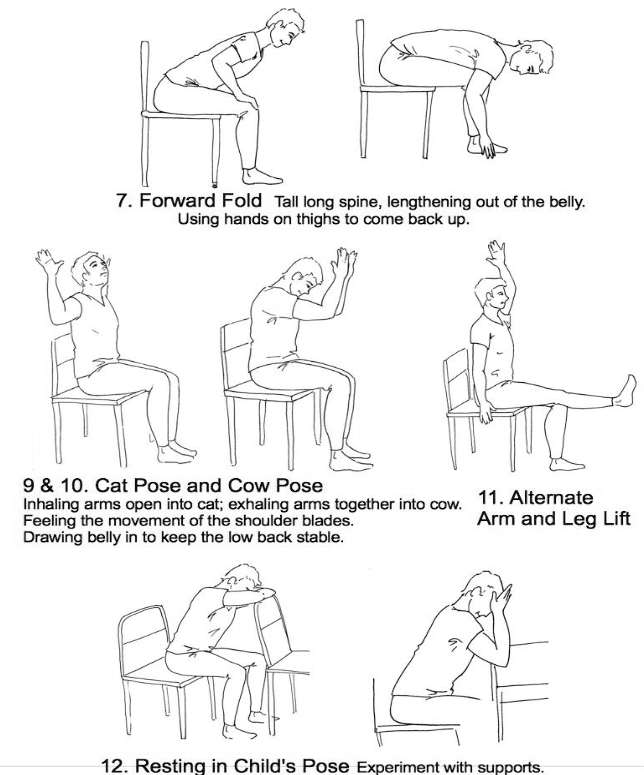

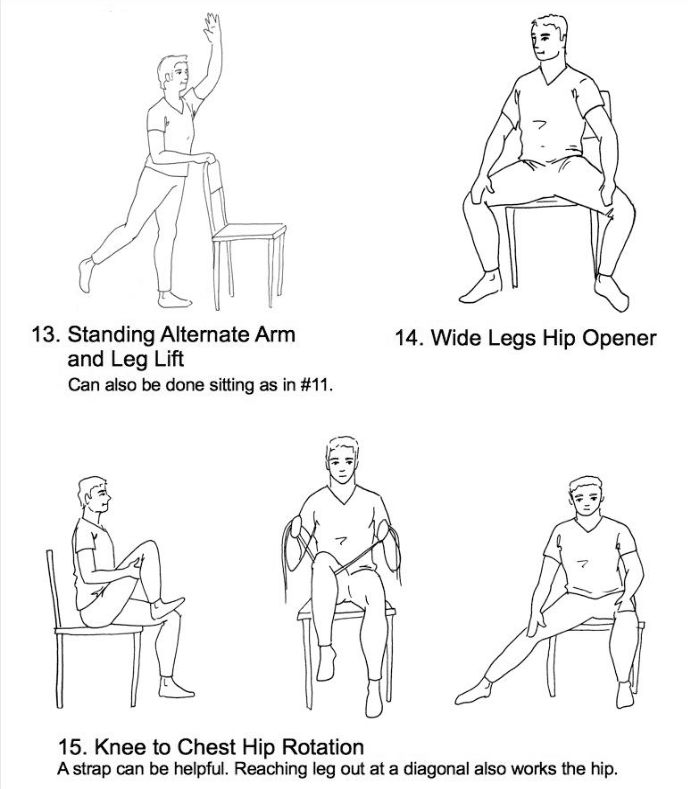

- Standing/sitting mindful movement

- Group discussion of current class topic and practices

- Home practice review & questions

- Closing practice

Home practice

- Formal: Body Scan 6 days this week using the recordings. At least on 30-minute Body Scan.

- Formal: Try Awareness of Breathing without a recording 10-15 minutes (recordings are available if you find them supportive).

- Informal: Pick a daily activity to do mindfully each day. For ideas see Mindfulness in Daily Life.

- Complete the Pleasant Events Calendar (next page) noting at least one event each day. You may find it easier to notice unpleasant events, for now focus on the pleasant!

Supplemental:

Read Our Brain's Negative Bias | Psychology Today. How to recognize and tame your cognitive distortions - Harvard Health

Watch the Videos Matt Killingsworth: Want to be happier? Stay in the moment | TED Talk (10 minutes) and Why Meditate? – Explained by Joseph Goldstein (6 minutes). The Power of Mindfulness: What You Practice Grows Stronger | Shauna Shapiro | TEDxWashingtonSquare(14 minutes),

[1] I made this word “perceptologist” up. There appears to actually be such a thing as Perceptology. However, this topic of study doesn’t seem to have to do with helping people get rid of distorted perceptions.

[2] If your perceptions cause suffering to you and/or those around you, the treatment and adjustment suggested here may not provide the desired results, your perceptions may be inflamed to the point where medical and or psychological intervention is required. Please don’t hesitate to talk to your doctor or mental therapist about your concerns.

Pleasant Events Calendar

Each day, note a pleasant event. Include a few notes on how the experience is experienced in the body, emotions, and thoughts. We will discuss in class.

| Pleasant Event | Reactions in body, emotion, thinking | |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | ||

| Tuesday | ||

| Wednesday | ||

| Thursday | ||

| Friday | ||

| Saturday | ||

| Sunday |

Class #3 – Theme: Being Present

There is a value in being present (build resilience; reduce reactivity; develop insight). Today’s theme is around attending to and investigating the way things are in the body and mind in the present moment through the practices of mindful movement and meditation. Pleasant and unpleasant sensations: how we define experience divides experience - can we return to wholeness and curiosity through mindful awareness?

The mind has a powerful way of sorting experience into what is pleasant and/or unpleasant. Powerful emotions, patterns, and habits are built around this sorting mechanism which may have evolutionary roots in avoiding danger. Likes. Dislikes. Preferences. Fears. Aversions. Desires. The mind seems to have a “negativity bias” whereby we perceive and remember negative experiences much more vividly than positive ones.

During the mindful movement and body scan practice start to inquire into sensations holding the question, “Is this pleasant or unpleasant?” And during the day start noticing if there is a sense of “leaning away” from the unpleasant and/or reaching for the pleasant. Notice this narrative emerge in the mind—how quickly and consistently does it arrive? Just holding the question “Is this pleasant? Is this unpleasant?” can powerfully shift patterns of reactivity.

Class Activity List

-

- Welcome, greeting,

- Opening practice, choosing an object of focus

- Mindful movement

- Brief guided body scan

- Sitting meditation: Attentional focus

- Small group discussion

- Large group discussion

- Brief walking practice

- Pleasant events review

- Home practice review & questions

- Closing practice

Home practice:

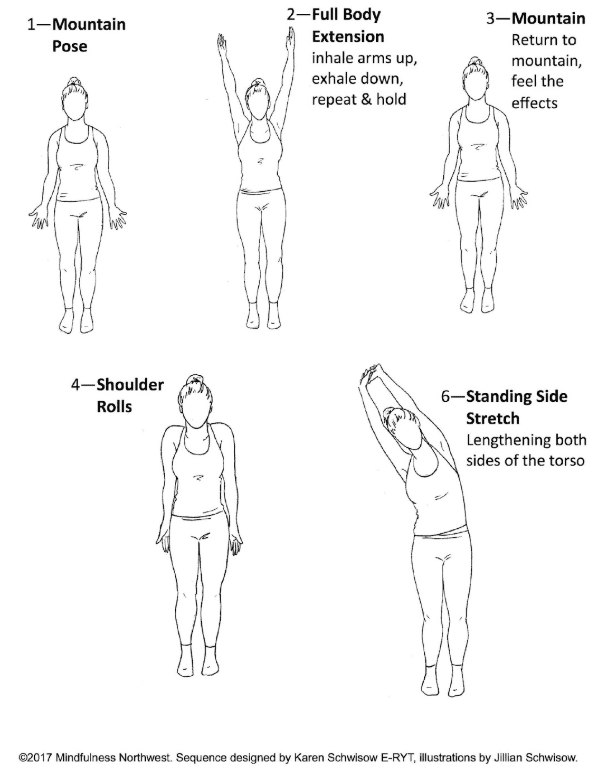

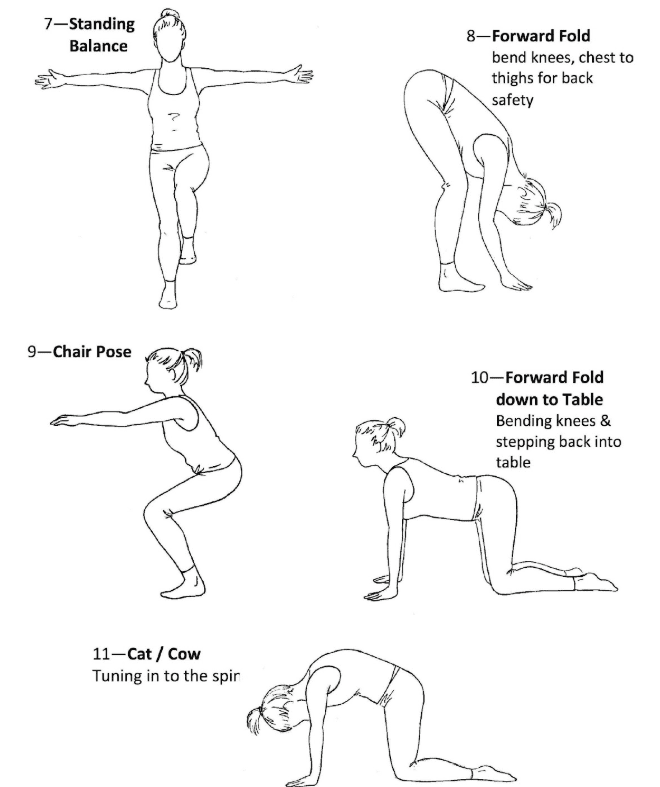

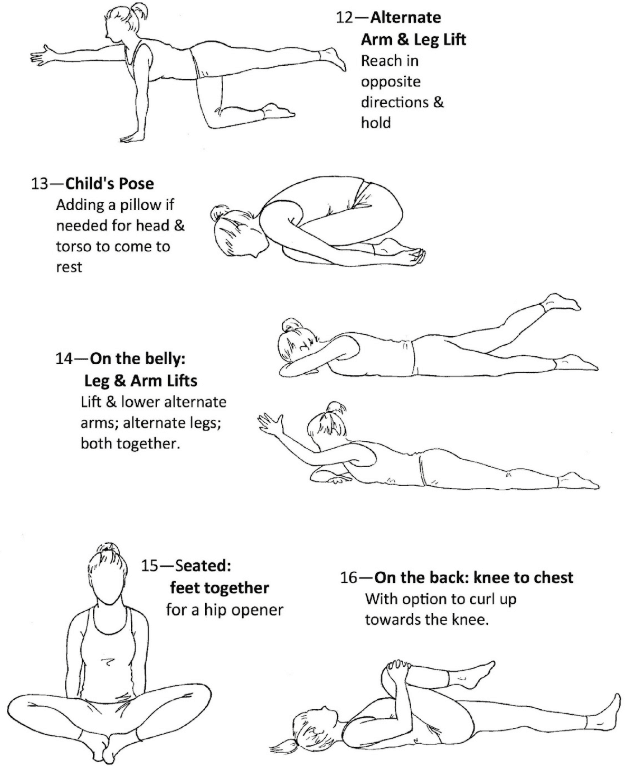

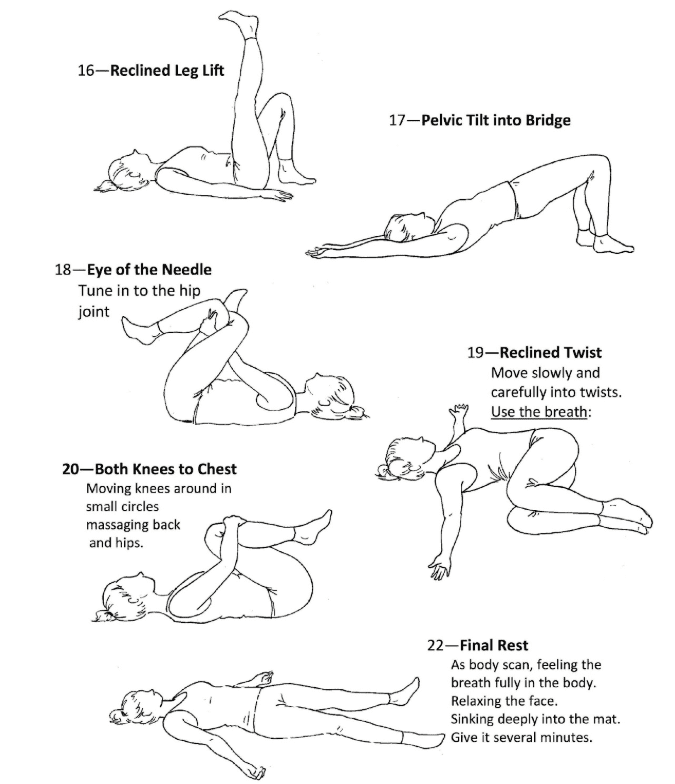

- Formal: Alternate the Mindful Movements with Gentle Mindful movement (35 minutes) and Body Scan (30 minutes, or try others) 6 days this week.

- Formal: Try Awareness of Breathing without a recording 10-15 minutes as close to daily as possible (recordings are available if you find them supportive).

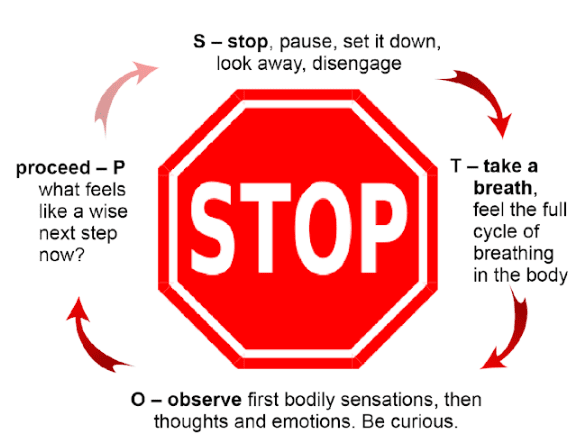

- Informal: Practices like STOP and Two Feet and a Breath can be helpful in weaving this practice into daily life. See the Purposeful Pause page in this manual.

Workbook:

- Complete the Unpleasant Events Calendar (next page) noting at least one event each day. See if you can observe unpleasant events and your response with curiosity and interest. What responses can you notice in body, emotions, and thinking?

Supplemental:

- Read Is This a Threat? in this manual.

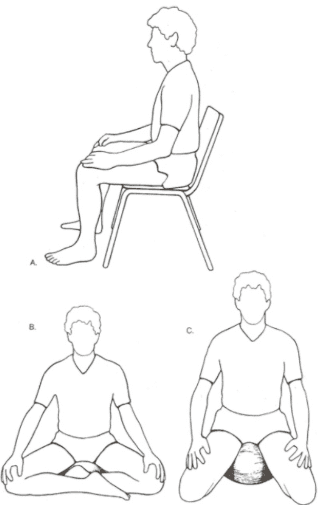

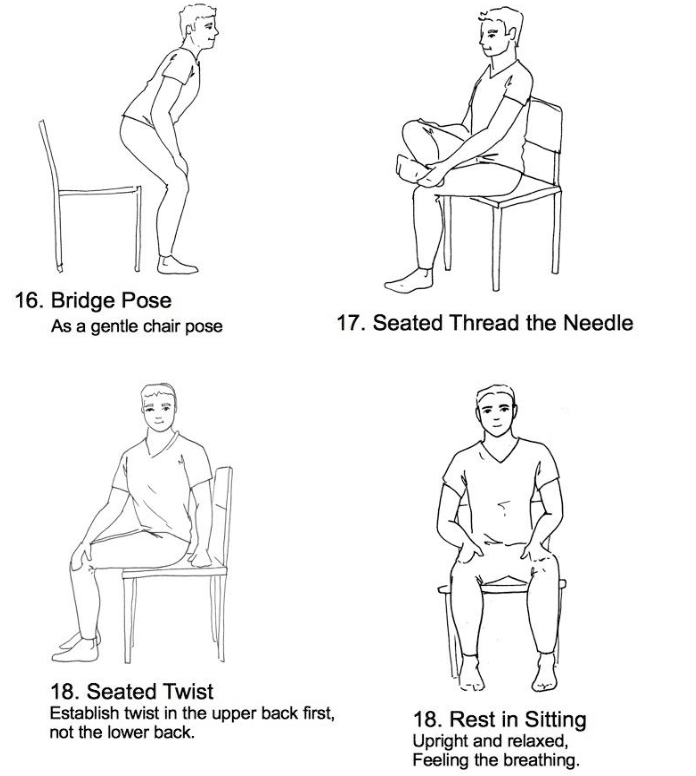

- Read Mindful Mindful movement and study mindful movement posture diagrams.

- Look at the Areas of Stress. What aspects of your life tend to be the most stressful? Where do you get stuck in reactivity?

Unpleasant Events Calendar

Each day, note an unpleasant event. Include a few notes on how the experience is experienced in the body, emotions, and thoughts. We will discuss in class.

| Unpleasant Event | Reactions in body, emotion, thinking | |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | ||

| Tuesday | ||

| Wednesday | ||

| Thursday | ||

| Friday | ||

| Saturday | ||

| Sunday |

Class #4 – Theme: Stress and Reaction

Mindfulness requires an increased willingness to experience more fully what we’re feeling on a moment by moment basis. The coping strategies upon which we rely may leave us with blind spots that formal and informal mindfulness practices start to illuminate. We use coping strategies (consciously and/or unconsciously) to avoid feeling what we are really feeling. What are some of your coping strategies? As we continue to re-establish the mind-body connection through our formal and informal practices a deeper understanding of these dynamics may also be revealed to us.

Social scientist Brené Brown suggests that there is a widespread inability to allow ourselves to be vulnerable enough to fully feel what we’re feeling. Her research suggests that addiction, debt, and a disconnection from others are a kind of numbing. And this numbing is a symptom of “vulnerability avoidance” (see the Resources/Video section of our website to watch her very interesting talk).

In your day-to-day life this week, consider if you can more fully feel what you’re feeling from moment to moment.

Class Activity List

-

- Welcome, greeting,

- Opening practice, choosing an object of focus

- Mindful movement

- Sitting meditation

- Small group discussion: Dyads/triads

- Large group discussion

- Unpleasant events review

- Home practice review & questions

- Closing practice

Home practice:

- Formal: Practice Mindful Movement with Gentle Mindful movement alternating with Awareness of Breathing (sitting mediation with an emphasis on breathing and awareness of the body) with the 25 minute recording or without guidance.

- Informal: Be aware of stress reactions and behaviors during the week, without trying to change them; notice feeling stuck, blocking, numbing, and shutting off to the moment.

Supplemental:

- Read Rumi’s poem aloud to yourself, The Guest House in the Poetry section.

- Read The Physiology of Stress.

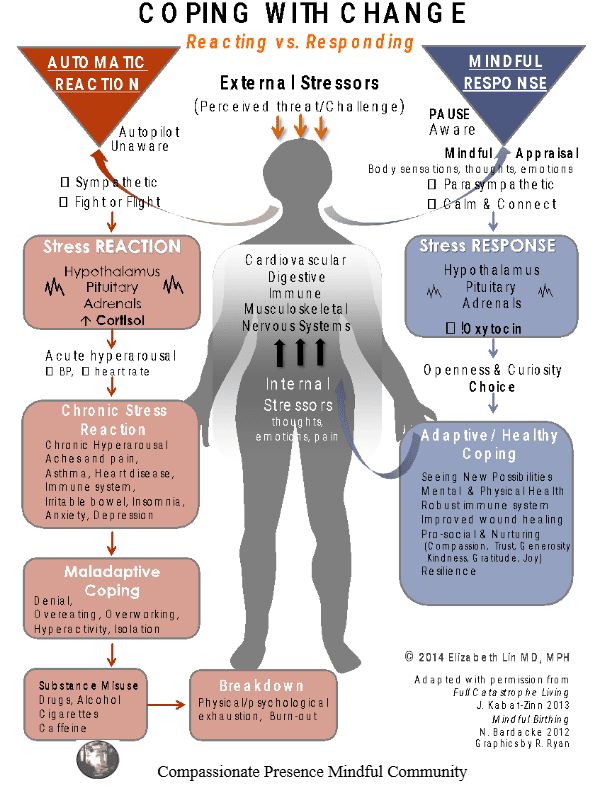

- Review Acceptance and Resistance and the two models of Stress Response Pathways.

- Watch the video “The Power of Vulnerability” by Brené Brown’s under Learn/Video on our website (20 minutes).

Class #5 – Theme: Reacting vs. Responding

(or “Is this a threat?”)

As we become more skilled at returning to the sensation of the breath in the body as a road back to the actual experience of the present moment, it may become possible to respond deliberately to stressors rather than just reacting automatically.

Interactions with others can be particularly charged and this week we begin an exploration of communication and focus more on interpersonal interactions.

Awareness of our thoughts as just thoughts is a particularly powerful tool. Increased awareness can help us determine when it’s worth our time and energy to reach mutual understanding and when it’s time to simply “drop the hat” and let it go.

How might mindfulness help us find ways to respond mindfully instead of reacting mindlessly and habitually as we navigate the challenges, concerns, and joys of the day?

Class Activity List

-

- Welcome, greeting, zoom logistics TDB

- Opening practice, choosing an object of focus TDB

- Standing movement TDB

- Sitting meditation (45 mins) KRISTIN

- Small group discussion: Dyads/triads

- Large group discussion: practice check-in NIKI

- Didactic: Stress Response TDB

- Midway reflection TDB

- Home practice review & questions TDB

- Closing practice TDB

Home practice:

Formal: We emphasize sitting practice starting this week. Try the longer sitting meditations called Open Awareness or Choice-less Awareness, alternating with body awareness practices (body scan or mindful movement).

Informal: Bring awareness to moments of reacting and explore options for responding with greater mindfulness, spaciousness and creativity. Remember the breath as an anchor, a way to heighten awareness of reactive tendencies, and a support to slow down and make more conscious choices.

Workbook:

Pay attention to communication and interaction with others and fill out the challenging communication calendar (next page). Reflect on a challenging or stressful communication experience each day. How did you respond? What can be learned about patterns and habits and underlying emotions involved in communicating with others?

Supplemental:

- Read A Note on Noting and Walking Meditation in this manual.

- Review the sections Communication Lens 1 and Communication Lens 2 and consider how they apply to your own investigation of communication.

- Try the RAIN practice recording (12 minutes) and consider if that method is helpful when strong emotions arise.

Challenging Communication Calendar

| Describe the challenging communication – what happened? | What did you experience during and after (body, emotion, thought) | What can you learn about patterns of reactivity and response from this? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | |||

| Tuesday | |||

| Wednesday | |||

| Thursday | |||

| Friday | |||

| Saturday | |||

| Sunday |

Class #6 – Theme: Skillful Communication

Our relationships with others can be a profound source of stress, as well as a powerful opportunity for growth. In mindfulness training we recognize the attitudes and internal processes we bring to each interaction with another and learn to take more responsibility for our own reactivity.

A subtle but powerful shift in attitude toward our thoughts as well as our emotions is to understand them as events that occur in the mind – objects of mind that come and go. This helps us to identify with our thoughts in a softer, more flexible way. Notice the huge difference between these two statements: (1) “I am so angry at you because of what you told me!” (2) “Anger is arising in response to what I heard.”

The possibility of understanding thoughts and emotions as experiences that are “not us” allows for spaciousness and increases our possibilities of response to others.

Communication and interaction can be a powerful source of stress and a deep source of joy and connection. How can we increase our skillfulness in communication so that we know our feelings and express them with greater awareness of ourselves and others?

Class Activity List

-

- Welcome, greeting, zoom logistics

- Opening practice, choosing an object of focus

- Standing mindful movement (NIKKI)

- Sitting meditation (45 mins)

- Small group discussion: Dyads/triads (skipped)

- Large group discussion (TDB)

- Difficult communication activity (KRISTIN & TDB)

- Home practice review & questions

- Closing practice

Home practice:

- Formal: Alternate longer sitting meditation (30-40 minutes, on your own or use the Open Awareness recording) with Mindful Movement with Gentle Mindful movement or The Body Scan (using recordings or on your own).

- Informal: practice mindful listening: listen mindfully to another for about 5 minutes with full attention.

- Manual: Read Unplug! and consider a week-long media fast in conjunction with our Day of Mindfulness. See full suggestions in the manual.

Supplemental:

- Try Loving-Kindness Meditation recording (15 minutes) at least once.

- Read aloud Mary Oliver’s poem Wild Geese in the Poetry section.

- Watch Shauna Shapiro on Mindfulness and Compassion in the Learning/Video section of the www.MindfulnessNorthwest.com website.

Day of Mindfulness – Extended Session

(4-5 hour retreat day)

Remember to bring a blanket and bag lunch to the Extended Session.

Open yourself to the unknown possibilities of engaging in continuous mindfulness practice – silently, along with a community of others who are currently taking or have previously taken classes with Mindfulness Northwest.

Suggestions:

- The practice of silence can be powerful (and at time intimidating). Our goal is to create a companionable silence together in which we give each other the gift of the space to have our own experience.

- Try not to strategize or watch the clock (keep watch and cell phone off). See if you can settle into the day one moment at a time.

- Throughout the day, try not to listen too much to inner judgments about whether the experience is, or was, meaningful or successful.

- Open to the possibility of just appreciating theses moments of your life – including pleasant and unpleasant moments.

- Honor the fact that you are making this powerful commitment to your own inner well-being.

Approximate Activity Sequence Setup, Introduction

- Awareness of Breathing

- Body Scan or Mindful movement

- Mindful Walking

- Listening Practice

- Lying Down Mindful movement

- Walking Meditation

- Silent lunch

- Awareness of Thoughts

- Walking Meditation

- Loving Kindness

- Standing Mindful movement

- Encouraging Words/Discussion

- Farewell

Reactions and thoughts before or after the Day of Mindfulness practice:

Class #7 – Theme: Taking Responsibility, Practicing Compassion

As we continue our exploration of mindfulness, we are learning that how we relate to and respond to the stressors of our lives is up to us. While we can’t control the external factors of life we have more influence over how we relate to our thinking, emotions, and reactions than we realized. And this ability to respond with more wisdom and clarity is itself influenced by many choices.

With greater awareness of how we are, we can also be more sympathetic to the plight of those around us. This week consider the maxim, “all people want happiness and freedom from suffering.” And yet everyone does experience difficulties and pain. Compassion is defined as the practice of noticing suffering in ourselves or others and being willing to help. Notice this week if you give or receive compassion to others, or to yourself.

Class Activity List

- Welcome, greeting, zoom logistics

- Opening practice, choosing an object of focus

- Standing mindful movement

- Sitting meditation (35 mins)

- Small group discussion: Dyads/triads

- Large group discussion/reflection on what we take in

- Fast, slow, open walking

- Home practice review & questions

- Closing practice

Home practice

- Formal: Choose any mindful practice to do every day this week. Consider practicing without recordings this week.

- Informal: Notice your attitudes and assumptions about yourself and others. Which kinds of judgments and conclusions does the mind draw? Is it possible to cultivate a more open-minded attitude of curiosity and "not knowing"?

- Workbook: Fill out the Moments of Compassion Calendar (next page).

Options:

- Experience one mindful meal this week really paying attention to the experience of eating (see Nine Steps to Mindful Eating for suggestions) and listen to the Savor Eating Meditation (4 minutes)

- Feel free to write a bit about your questions, intentions, and musings as they relate to mindfulness practice, the class, and your life.

- Watch the video “How Mindfulness Cultivates Compassion” by Shauna Shapiro under Learn/Video on the website (16 minutes).

Moments of Compassion Calendar

| Describe a moment of compassion: towards others, from others, or for yourself. | What did you experience during and after (body, emotion, thought) | What can you learn about from this? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | |||

| Tuesday | |||

| Wednesday | |||

| Thursday | |||

| Friday | |||

| Saturday | |||

| Sunday |

Class #8 – Theme: Continuing the Practice

Continuing the Practice as a Regular Part of Life.

“The eighth week is the rest of your life.”

The theme of our last class is celebration and intentions setting. Let’s celebrate together our commitment to this process of change and growth. Let’s celebrate the support we received from each other, from the instructor, and from these practices. Let’s even celebrate the challenges and problems we may have experienced. That’s where the learning can be the richest.

And let’s consider where we go from here. We’ll explore possibilities for future practice and resources that will help us going forward.

Class Activity List

-

- Welcome, greeting, zoom logistics

- Sitting meditation

- Body scan

- Discussion of home practice

- Guided Reflection

- Evaluations

- Writing letter to future self

- Home practice & Next steps

- Final sharing and Closing the Circle

- Goodbyes

Home practice

- Consider how you will integrate mindfulness practice into your daily life—both formal and informal practices.

- Practice mindfulness as a way of life for the rest of your life! ☺

Reading:

- At the end of the manual we’ve included several resources to help you going forward. Take a look at Maintaining a daily practice – a few suggestions, Levels of Practice, Community Mindfulness Practice Groups, and the Reading List!

- Read aloud Portia Nelson’s poem, Autobiography in Five Short Chapters, in the Poetry section. Does this poem describe your process of habit change?

Supplemental Reading Material

What is Mindfulness Practice?

by Tim Burnett, written for this manual, January 2013

“Mindfulness is paying attention, on purpose, to the present moment, non-judgmentally.” Jon Kabat-Zinn,(1990).

The practice of mindfulness encourages us to pay attention to the process of our experience – not just the content. We learn to study the feeling and flow of experience and be less caught on our opinions and desires around how we feel experience should be. In other words, mindfulness practices support us in taking a small but important step back – a “breathing space.”

When something happens, anything at all, the mind and our senses have a fast and complex interaction. The sum of all of these momentary experiences is our experience of living. You could even say that mind’s ongoing narrative summary of everything that is happening, has happened, and is imagined to be coming soon, is our experience of self. Too often all we notice is the final result of this interaction and miss the complex unfolding that just happened.

All of this doesn’t happen in mental isolation. Our engagement with experience is embodied. When events happen, they happen through the body. And the body is hard-wired for vigilance; ready to respond to threats. If the threat protection mechanisms of the body are triggered a rapid cascade of events in many systems (nervous, hormonal, digestive) revs us up quickly and readies us to fight, run, or freeze. Our higher level cognitive systems have been shown to go into a restricted mode in these times lest we ruin our chances for survival by standing there trying to figure things out when we should be running for the hills.

Mindfulness practice is a way of exploring the processes that often run our lives. It is a way of bringing these semi-automatic processes into the open and working with them in a way that usually leads to:

- less time spent in “automatic pilot”

- more awareness of the details of experience

- less energy spent worrying about the future or ruminating about the past

- greater resilience and an increased ability to moderate our reactivity

- reduced risk of a long list of stress-related diseases

- an increased sense of presence – really being there for ourselves and others

- an increase in a spacious type of joy which is able to hold life’s ups and downs more fully and kindly, including experiences we do not like

Fundamentally mindfulness practice works by bringing attention back to the present moment.

We can think of attention as a theatrical spotlight. In the back of the darkened theater the spotlight is on casting its circle of light somewhere on the stage. The part of the stage that’s lit up is what is accessible to our conscious awareness. The spotlight of attention is very compelling and when it’s focused in on something that is often all we are aware of.

The spotlight of attention might be focused on a sensory event, something we are seeing or hearing for example, but all too often the spotlight of attention is focused on a mental “event.” Our attention is caught by a memory, a worry, or an anxious vision of the future. Have you had the experience of the mind being so caught by this ruminative kind of thinking that you hardly notice your surroundings? Have you pulled up in the car at your destination not remembering how exactly you got there? This capacity of mind to have the spotlight of attention completely trapped – enraptured even – by the thinking is sometimes called being caught in “automatic pilot.”

We don’t have to be run by the thoughts and memories that happen to pop into our minds distracting us from our work and activities. We can move the spotlight of attention. We can choose what to aim it at. We can also choose how tightly to focus the spotlight. Zooming in a detail in our activity at work, or open it up wide to take in a sunset or the experience of being relaxed and happy with a loved one not worrying about anything in particular.

And yet all too often we lose track of this. Our attention veers off – out of control. A funny look from a colleague, a car veering in front of us in the road, a memory, a worry, many different events can trigger us to forget all about our powerful ability to influence attention and we are lost to the present moment again.

Mindfulness practice has two key elements: formal and informal. Formal mindfulness practice is a central element of our time together in mindfulness class. In formal practice we take up particular instructions for working with attention and train ourselves to attend to something steadily for a structured period of time. We set everything else aside and just practice.

In formal practice we also train ourselves in a positive way of relating to our habits of wandering attention. When our attention drifts away we work to bring it back gently and kindly, with a spirit of steadiness and persistence. With less blame and recrimination. And in the simplified circumstances we create during formal practice it’s more obvious when attention has drifted away. Much more obvious than in the middle of our busy lives.

You could say that the root of mindfulness is developing the ability to remember. To remember that attention is in operation. To remember that there’s more happening on stage than whatever the spotlight is currently illuminating. To remember that we are sitting behind the spotlight of our attention and able to direct it to some extent. To remember that in the darkness at the edges of the stage are many possibilities, some known, some not. We can touch into the many dimensions to our lives beyond our usual story line.

As we develop the ability to return attention to present-moment phenomena we are often surprised to see that whatever it is that’s happening is not the same as what we were worried about. Often actual experience is richer, more interesting, and less problematic than we imagined. What a relief this can be!

We can even notice a lack of reactivity, less stress, fewer times when we make assumptions that tie our self in knots. And when we do get tangled, with practice we can identify our “tangled-ness” and take it a little less personally and a little less seriously. We develop more patience with our conditioning and habit patterns.

Where formal mindfulness practice is a kind of intensive “lab of attention,” informal practices help us to bring this work out into the world. Into the middle of our day. Into those moments that can be so loaded for us. There are many ways to remember to practice mindfulness in daily life. Pausing to take a breath before entering a new room where something requires your full attention, for example. We will discuss others in class. And we also discuss the ways in which this process is non-linear, organic, and often surprising.

Becoming more aware of the embodied nature of experience is profoundly helpful. We learn to listen more to our body. We feel the tightness in our shoulders; the pinch in our gut. Rather than soldiering on we wonder at this. We pause. We breathe into it. We listen to the “wisdom” of the body and appreciate the body as a kind of early warning system. Often well before the mind has cottoned on to what is happening our body is letting us know that something is amiss. And responding sooner than later to this helps us right the ship well before it capsizes.

Mindfulness is a creative re-engagement with our actual experience. We put aside our sense of knowing exactly who we are and what is happening. We set all of that history and personality down, or at least hold is a little more lightly, and we take a look. A fresh look. “I wonder what is happening here?” With fresh eyes we re-inhabit our life. And this freshness, this openness, brings us great gifts, even in the middle of our most challenging moments.

One way of thinking of this life is that it’s all happening in this moment. In this very moment. And if we are lost in some other moment we are very literally missing our life.

“Make the moment vital and worth living… do not let it slip away unnoticed and unused.” Martha Graham

Acceptance and Resistance

S = P x R

Suffering equals Pain times Resistance

(Pain is inevitable in life; resistance is something added)

Accept pain for what it is because it does exist. Pain includes both physical and emotional pain.

Resisting our pain worsens our suffering. Resistance can include: Shoulds, Coulds, Woulds, Denial, Pushing Away, Holding on to, Guilt, Judging, Negative Self-Talk and Rumination.

Reducing our resistance to the pain we experience either reduces or all together rids us of our suffering.

The Two Darts

The Buddhist teaching story of the two darts is another way of expressing this idea.

The first dart is the unavoidable pains and difficulties of a life. We stub our toe, someone is grumpy with us, all the way up to illness, old age, and death. The first dart is the painful experience of receiving what we don’t want or not getting what we do desire.

The second dart is a reaction of some kind. A wish, a regret, anger, something that the mind adds to the experience arising from our conditioning and history. While we can never avoid all of the first darts, we can do more than we think we can to reduce how many of these second darts we throw at ourselves.

In Between Stimulus and Response…

-Victor Frankl, Psychologist, Author and Holocaust Survivor

“In between stimulus and response there is a space.

In that space is our power to choose our response.

In our response lies our growth and freedom.”

Opening & Closing and the Three Rings of Growth

The process of growth and change isn’t linear. We can’t always maintain a positive attitude and a growth mindset. There are times when we have the resources to open and grow;

and times when those resources aren’t available and we need to close.

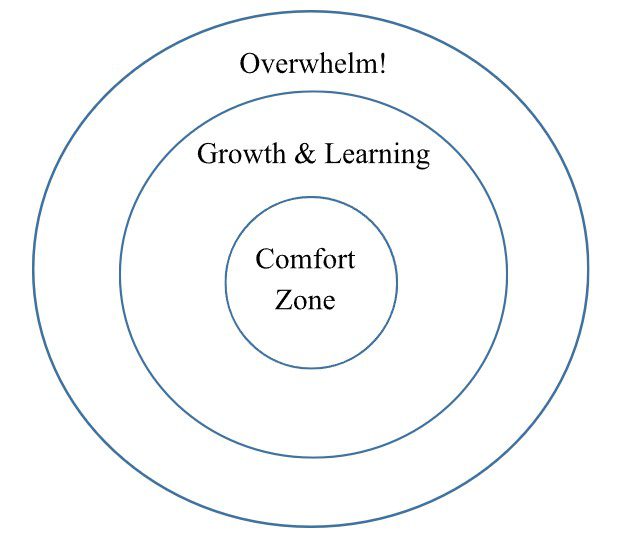

We could think of our experience as moving between three interlocking circles as depicted below. Our need to close sometimes may have us pulling into the Comfort Zone in the center. Our ability to open may allow us move out into the area of Growth & Learning. But if we push it too hard and too far we’re into the stressful zone of Overwhelm! and we can’t learn much there.

Questions to consider:

What does it look like for you when you are available and open? What does it feel like for you when you need to close? What kinds of self-care activities are helpful when you need to close? What kind of encouragement and resources helps you emerge again from the Comfort Zone into Growth & Learning? How do you know when you’ve pushed it too far and you’re floundering in the area of Overwhelm?

The Purposeful Pause

STOP – Pausing in response….

Two Feet and a Breath – Pausing in Preparation

This practice developed for doctors to help them return to mindfulness before entering an exam room to interact with a new patient is useful for anyone entering a room where something new is happening. Two Feet and a Breath helps us be more fully present in a the new situation whether it’s a meeting at work or reminding our child of their homework.

Before entering a room:

- Pause and feel your two feet on the floor.

- Take one mindful breath.

- Proceed.

Meeting Difficult Moments with RAIN

The acronym R.A.I.N. can remind us of a wise way to meet difficult situations with mindfulness and kindness towards ourselves and others.

R Recognize what is happening

A Allow and Accept – What is, is

I Investigate inner experience, dropping out of the story line, and into the feeling in the body, emotions, heart, and mind

N Non-identification – Invite yourself to see even the more powerful emotions as events in the mind and heart with less “me” in them.

RAIN directly de-conditions the habitual ways in which you resist your moment-to-moment experience. It doesn’t matter whether you resist “what is” by lashing out in anger, by having a cigarette, or by getting immersed in obsessive thinking. Your attempt to control the life within and around you actually cuts you off from your own heart and from this living world. RAIN begins to undo these unconscious patterns as soon as we take the first step.

R – Recognize what is happening: “Name it and you tame it,” the saying goes. How would you describe your inner experience?

A – Allow and Accept – What is, is: Are resistance and judgment present? Can you soften around those “extras” and turn towards what’s here now with patience and acceptance?

I – Investigate inner experience: Our mindfulness training is critical here. Drop into breathing for a moment to create the space needed for this subtle work, then move into a brief body scan and label the chief thoughts and emotions in the mind. What’s happening?

N – Non-identification: It’s hard to underestimate the difference between our usual “What you did made me so angry!” and “I feel anger arising.” If it’s “me” who’s angry we are the anger, and the anger is us, and it’s so easy to blame ourselves and others. We’re in our heads in a way that leads to separation and suffering. With the inner step back that mindfulness allows we can see anger, or any other strong experience, as just that: an experience. One metaphor often used is the weather. We prefer sun over rain but we don’t take it personally when it’s drizzling out. It’s just rain. In the same way, with practice, we realize that it’s just anger. Unpleasant weather to be sure, but something we seek to respond wisely to.

We don’t need to be an “angry person.”

The Science of Mindfulness

Adapted from A Clinician’s Guide to Teaching Mindfulness by Chrstiane Wolf & J. Greg Serpa

Research citations available on request

Scientific work on mindfulness and meditation is a small but fast growing area of research. While it’s important to remember that mindfulness is not a cure-all, it’s helpful to know that science is validating the practice of mindfulness in several ways.

Mindfulness improves symptoms of many conditions. Many studies show improvement in psychological and physiological functioning such as decreases in depression, anxiety, and pain and increases in quality-of-life measures, sleep, and functional status.

One large meta-analysis from Boston University found (Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt and Oh 2010) that mindfulness had a moderate effect size in improving anxiety and depressive symptoms and that for patients with both anxiety and mood issues mindfulness training had a larger effect size, and these changes are robust and maintained over time. Another meta-analysis (Goyal et al, 2014) showed improvements in depression, anxiety, and pain from mindfulness.

Mindfulness has also been effective in addressing the psychological stressors and coping in chronic and life-threatening illnesses (Carlson 2012). In oncology, studies have shown mindfulness associated with improvement in mood and reduction of stress (Speca et al, 2000) and improvements in quality of life (Lerman et al, 2012) for patients in treatment for cancer.

Research also supports mindfulness for coping with rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, HIV/AIDs, irritable bowel syndrome, organ transplant, chronic pain, and fibromyalgia (Carlson 2012).

Mindfulness and biological markers of health. Mindfulness practice can have a remarkable effect on general body functioning as reflected in biomarkers.

Cortisol, the primary stress hormone from the adrenal glands, has long been associated with immunosuppression (Spiegel et al 1998). Changes in salivary and serum cortisol levels are an effective biomarker indicating a reduction in stress from a mindfulness practice (Matousek, et al 2009).

Other studies looking at other biomarkers include a study of brain and immunological response to the influenza vaccine (Davidson et al, 2003). In this study, subjects who had completed an MBSR class (against a wait-list control) showed greater left anterior frontal lobe activation (a brain region associated with positive mood) and stronger immune response to the influenza vaccine. Further, a relationship between the left anterior activation and immune response was found: the greater the shift in the brain the greater the immune response.

Fascinating recent work has been done on mindfulness and cellular aging. With the discovery of telomeres – the caps on the ends of chromosomes where our genes reside – and the protective associated enzyme telomerase, researchers can see potential benefits from mindfulness on cellular aging. Telomeres protect our chromosomes during replication and are degraded by stress (Epel et al, 2009). Mindfulness can have a beneficial impact on telomere length by reducing the cognitive stress and arousal that in turn reduces telomere length. One study of participants in a three-month meditation retreat (Jacobs et al, 2011 – The Shamata Project) showed that decreases in negative affect and other positive psychological changes were linked to increased telomerase activity. This study suggests that meditation can reduce aging at the cellular level!

Mindfulness and neuroplasticity. Although easily over-reported (“Rewire your brain for happiness in just eight weeks!”), exciting findings in the neuroscience of meditation are accumulating. It’s now well understood that how we use our brains changes the function and structure of our brains.

The first study to explore structural brain changes in meditators found that experienced meditators had cortical thickening in areas related to emotional, sensory, and cognitive processing compared to nonmeditators (Lazar et al, 2005). Subsequent studies have found a wide range of brain changes including changes in the anterior cingulate, associated with self-regulation, after just four weeks of daily mindfulness practice (Tang et al, 2012). Other studies have found changes in gray matter density, the actual number of brain cells in the hippocampus, after eight weeks of MBSR (Holzel et al, 2011). Another study (Luders et al, 2009) found that experienced meditators had greater cell volumes in the right prefrontal cortex, an area associated with emotional regulation, than non-meditators do.

Mindfulness and compassion. Simply being aware in the active curious accepting way we practice in class seems to naturally lead to increases in positive affect and pro-social behavior (Shapiro et al, 2007). Findings here include evidence for a compassion instinct (Keltner, Marsh & Smith, 2010) and that compassion is essential for our social connections which are in turn essential to our physical and emotional well-being (Seppala, et al, 2013). Increases in compassion have been linked to lower levels of inflammation (Fredrickson et al, 2013) and to a longer life (Brown et al, 2009; Konrath et al, 2012).

With the definition by Kristen Neff of self-compassion as a research construct (Neff, 2003a) and the creation of research instruments to examine compassion towards our self, associations between mindfulness and self-compassion and self-care have been found. Examples include reduction in tobacco use (Kelly et al, 2009), reduction in alcohol use (Brooks et al, 2012) increases in positive, accepting, and creative responses to life stressors such as aging (Allen & Leary, 2013) and serious illness (Brion, Leary, & Drabkin, 2014). While compassion and self-compassion do seem to arise naturally from mindfulness training, they can also be trained in more directly with such mindfulness-oriented courses as Compassion Cultivation Training and Mindful Self-Compassion.

The “Negativity Bias” of the Brain

by Rick Hanson & Richard Mendius, Buddha’s Brain: the practical neuroscience of happiness.

The brain typically detects negative information faster than positive information. Take facial expressions, a primary signal of threat or opportunity for a social animal like us: fearful faces are perceived much more rapidly than happy or neutral ones, probably fast-tracked by the amygdala (Yang, Zald,’ and Blake 2007). In fact, even when researchers make fearful faces invisible to conscious awareness, the amygdala still lights up (Jiang and He 2006). The brain is drawn to bad news.

When an event is flagged as negative, the hippocampus makes sure it’s stored carefully for future reference. Once burned, twice shy. Your brain is like Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positive ones—even though most of your experiences are probably neutral or positive.

Negative events generally have more impact than positive ones. For example, it’s easy to acquire feelings of learned helplessness from a few failures, but hard to undo those feelings, even with many successes (Seligman 2006). People will do more to avoid a loss than to acquire a comparable gain (Baumeister et al. 2001).

Compared to lottery winners, accident victims usually take longer to return to their original baseline of happiness (Brickman, Coates, and Janoff-Bulman 1978).

Bad information about a person carries more weight than good information (Peeters and Czapinski 1990), and in relationships, it typically takes about five positive interactions to overcome the effects of a single negative one (Gottman 1995).

Is this a threat?

by Rick Hanson and Richard Mendius, Buddha’s Brain

How does your brain decide if something should be approached or avoided? Let’s say you’re walking in the woods; you round a bend and suddenly see a curvy shape on the ground right smack in front of you. To simplify a complex process, during the first few tenths of a second, light bouncing off this curved object is sent to the occipital cortex (which handles visual information) for processing into a meaningful image.

Then the occipital cortex sends representations of this image in two directions: to the hippocampus, for evaluation as a potential threat or opportunity, and to the PFC (pre-frontal cortex) and other parts of the brain for more sophisticated—and time-consuming—analysis.

Just in case, your hippocampus immediately compares the image to its short list of jump-first think-later dangers. It quickly finds curvy shapes on its danger list, causing it to send a high priority alert to your amygdala: “Watch out!” The amygdala—which is like an alarm bell—then pulses both a general warning throughout your brain and a special fast-track signal to your fight-or-flight neural and hormonal systems (Rasia-Filho, Londero, and Achaval 2000).

We’ll explore the details of the fight-or-flight cascade later [see The Physiology of Stress, next page]; the point here is that a second or so after you spot the curving shape, you jump back in alarm.

Meanwhile, the powerful but relatively slow PFC has been pulling information out of long-term memory to figure out whether the darn thing is a snake or a stick. As a few more seconds tick by, the PFC zeros in on the object’s inert nature—and the fact that several people ahead of you walked past it without saying anything— and concludes that it’s only a stick.

Throughout this episode, everything you experienced was either pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral.

At first there were neutral or pleasant sights as you strolled along the path, then unpleasant fear at a potential snake, and finally pleasant relief at the realization that it was a stick. That aspect of experience – whether it is pleasant, unpleasant or neutral – is called, in Buddhism, its feeling tone (or, in Western psychology its hedonic tone). The feeling tone is produced mainly by your amygdala (LeDoux 1995) and then broadcast widely. It’s a simple but effective way to tell your brain as a whole what to do each moment: approach pleasant carrots, avoid unpleasant sticks, and move on from anything else.

From Buddha’s Brain: the practical neuroscience of happiness, love & wisdom. Rick Hanson, PhD and Richard Mendius, MD. (New Harbinger 2009)

The Physiology of Stress

by Rick Hanson and Richard Mendius, Buddha’s Brain

Suffering is not abstract or conceptual. It’s embodied: you feel it in your body, and it proceeds through bodily mechanisms. Understanding the physical machinery of suffering will help you see it increasingly as an impersonal condition—unpleasant to be sure, but not worth getting upset about, which would just bring more second darts.*

Suffering cascades through your body via the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPAA) of the endocrine (hormonal) system. Let’s unscramble this alphabet soup to see how it all works. While the SNS and HPAA are anatomically distinct, they are so intertwined that they’re best described together, as an integrated system. And we’ll focus on reactions dominated by an aversion to sticks (e.g., fear, anger) rather than a grasping for carrots, since aversive reactions usually have a bigger impact due to the negativity bias of the brain.

Something happens. It might be a car suddenly cutting you off, a put-down from a coworker, or even just a worrisome thought. Social and emotional conditions can pack a wallop like physical ones since psychological pain draws on many of the same neural networks as physical pain (Eisenberger and Lieberman 2004); this is why getting rejected can feel as bad as a root canal. Even just anticipating a challenging event—such as giving a talk next week— can have as much impact as living through it for real.

Whatever the source of the threat, the amygdala sounds the alarm, setting off several reactions:

The thalamus—the relay station in the middle of your head—sends a “Wake up!” signal to your brain stem, which in turn releases stimulating norepinephrine throughout your brain.

The SNS sends signals to the major organs and muscle groups in your body, readying them for fighting or fleeing.

The hypothalamus—the brain’s primary regulator of the endocrine system—prompts the pituitary gland to signal the adrenal glands to release the “stress hormones” epinephrine (adrenaline) and cortisol.

Within a second or two of the initial alarm, your brain is on red alert, your SNS is lit up like a Christmas tree, and stress hormones are washing through your blood. In other words, you’re at least a little upset. What’s going on in your body?

Epinephrine increases your heart rate (so your heart can move more blood) and dilates your pupils (so your eyes gather more light). Norepinephrine shunts blood to large muscle groups. Meanwhile, the bronchioles of your lungs dilate for increased gas exchange— enabling you to hit harder or run faster.

Cortisol suppresses the immune system to reduce inflammation from wounds. It also revs up stress reactions in two circular ways: First, it causes the brain stem to stimulate the amygdala further, which increases amygdala activation of the SNS/HPAA system—which produces more cortisol. Second, cortisol suppresses hippocampal activity (which normally inhibits the amygdala); this takes the brakes off the amygdala, leading to yet more cortisol.

Reproduction is sidelined—no time for sex when you’re running for cover. The same for digestion: salivation decreases and peristalsis slows down, so your mouth feels dry and you become constipated.

Your emotions intensify, organizing and mobilizing the whole brain for action. SNS/HPAA arousal stimulates the amygdala, which is hardwired to focus on negative information and react intensely to it. Consequently, feeling stressed sets you up for fear and anger.

As limbic and endocrine activation increases, the relative strength of executive control from the PFC (pre-frontal cortex) declines. It’s like being in a car with a runaway accelerator: the driver has less control over her vehicle. Further, the PFC is also affected by SNS/HPAA arousal, which pushes appraisals, attributions of others’ intentions, and priorities in a negative direction: now the driver of the careening car thinks everybody else is an idiot.

For example, consider the difference between your take on a situation when you’re upset and your thoughts about it later when you’re calmer. In the harsh physical and social environments in which we evolved, this activation of multiple bodily systems helped our ancestors survive. But what’s the cost of this today, with the chronic low- grade stresses of modern life?

* The “first dart, second dart” is a reference to a teaching story from the Buddha. A difficult or painful experience is the unavoidable “first dart” of experience. The unneeded suffering caused by reactivity and unmitigated stress responses, including maladaptive coping strategies, and distorted thinking, are the “second dart.” While we cannot wholely avoid the first darts of life, we can reduce habitual tendencies to throw the second darts at ourselves.

Stress Response Pathways

RESETTING OUR MINDSETS ABOUT STRESS

New research cited by Kelly McGonigal in The Upside of Stress suggests that our experiences of stress are altered by our mindset: conscious and/or subconscious thought patterns and beliefs about stress. (“It’s killing me” “I just can’t take one more thing.” “This will tough but I’ll try.”) She explains how helpful it is to let go of a mindset in which we feel threatened or overwhelmed by stress and to move into mindsets that involve facing the stress, seeking support and seeing difficulty as possibility.

In formal and informal mindfulness practices, we can become more aware of thoughts and beliefs underlying our mindsets and transform them into healthier, more proactive mindsets.

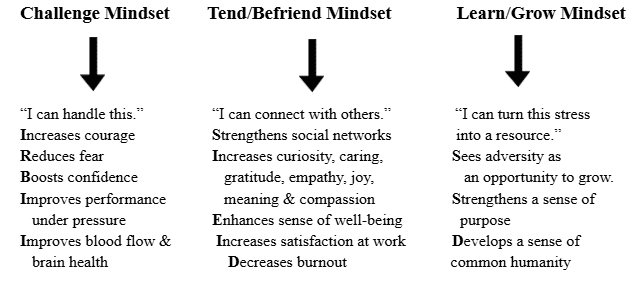

McGonigal describes three healthy, proactive mindsets in her book: the Challenge Mindset, the Tend/Befriend Mindset, and the Learn/Grow Mindset.

Adapted from The Upside of Stress, Kelly McGonigal, PhD, 2015

Mindfulness in Daily Life

by Saki Santorelli, Center for Mindfulness, U. Mass.

Choose a mindful activity to practice for the week and remember to practice awareness of body sensations, thoughts, and feelings while performing the activity. You may select from the list below or choose an activity of your own.

Washing hands: Consider from where the water comes, and how valuable it is in our arid environment. Be aware of the posture of your body, the feelings of the water, the soap, the movement of your hands. Breathe!

Stopping at a red light: Allow this to be a moment to pause, breathe, look at the sky, look at people. Become aware of the posture of sitting, notice the sensation of your hands on the wheel. How tightly are you holding the wheel? Be aware of your shoulders and back. Notice the pressure of your buttocks on the seat, your thighs, the contact your feet make with the floor, the brake. What sort of thoughts and feelings arise? What is your mood?

Looking at a clock or your watch, remember to breathe. Try putting your watch on the other arm as another way to pause. Notice how it feels when things are slightly different.

When the telephone rings, instead of rushing to answer it, allow yourself to pause for the first three rings, relax your face with a half smile, and breathe. Feel your arms reaching for the phone, the contact your hand makes with the plastic, how the receiver feels against the ear.

Washing dishes: Notice your posture, how your body moves, the look and feel of the dishes: the feel of the water, how it looks and sounds. Are you doing dishes slowly or rushing to get done? Be aware of your mood. Breathe.

Brushing your teeth: Notice how your hands hold the toothbrush, the movement of your arm, the sound of the brush on your teeth. Taste the toothpaste.

Taking a shower: Be aware of water: its temperature, where it hits your body. Be aware of: posture, movements, your mood.

Eating one mindful meal a day, perhaps breakfast or lunch. Notice how you are sitting (or standing). See the food, the shapes and colors. Smell it. Pause to consider from where it came and how it ultimately reached your table. Notice any feelings of anticipation. Be aware of reaching for the food, bringing it to your mouth. Be with the taste and texture of the food as you chew. How do you swallow? Notice any impulse to rush through this bite in order to go on with the next. Notice thoughts and feelings that arise. What is your mood? How is your breathing?

Reaching, touching, turning a door knob, Notice when opening the door and passing through the doorway. Breathe. A transition.

Driving: Turn the radio off and be with driving. Awareness of your posture, the pressure of your hands on the steering wheel, your buttocks on the seat and your foot on the gas pedal/brake. Notice what parts of your body are tense or relaxed. What is your breathing like? Be with sights and sounds as they arise and pass away. Use beginner’s mind to see your old route with fresh eyes. (Or you might try a new route.)

Drive slowly: Stay in the right lane and go 55 miles an hour. Breathe.

When you go to work: Look into the eyes of a co-worker and say, “good morning.” Breathe.

When dressing and undressing: Notice your posture and how you reach for the clothes. How they feel on your skin as you slip them on or off. Breathe.

Use those moments of walking (in the office, at home, to and from your car, shopping, etc.) as mediation. Be with your posture, the feel of your body moving, how your legs and arms move. The feel of your feet contacting the ground. Your breathing. Sights and sounds. Thoughts and moods.

Shopping meditation: Be aware of your intention, what you plan to buy. Notice how your attention is being pulled by different objects, notice the desire to have or own something. See if you can pause and ask yourself if you need this or if it is enough to look at this beautiful object in the store. (Imagine stores as art museums.) When food shopping, be aware of what foods are calling you. Is it your body that is hungry for them, or your mind?

Checking your phone: When the urge to check for new messages arises, study it for a minute. Is this a time when you really need to check? What is motivating the impulse to feel connected? Not that we should never check, but perhaps a bit less often and perhaps some of the times we can simply use that urge as a mindfulness cue to pause and breathe and feel what we’re feeling.

Yesterday is but a memory and tomorrow only a vision. But today well lived makes every yesterday a memory of happiness and every tomorrow a vision of hope.” –ancient Sanskrit poem

Unplug! (What do you feed your mind?)

adapted from How to Train a Wild Elephant by Jan Chozen Bays, MD

The Challenge: A One Week Media Fast

For one week: do not take in any news and social media. Do not listen to the radio, iPod, or CDs; don’t watch TV, films, or videos; don’t read newspapers or news magazines (whether online or in print form); don’t surf the Internet; and don’t check on social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter.

You don’t have to plug your ears if someone tells you about a news event, but do avoid being drawn into a conversation about the news. If people insist, tell them about your unusual fast. You may, of course, do reading that is necessary for work or school.

What do you do instead? Part of this mindfulness practice is discovering alternatives to consuming media. Hint: do something with your own hands and your own body.

Reminding Yourself:

Cover the TV or computer with a sheet, or put a sign on your car radio and computer screen reminding you “No News This Week.”

Reflections:

Our senses are constantly drawing our attention outward. In our media-crazed society we are bombarded by sounds, smells, bright colors, and are constantly exposed either to shiny, alluring things that are supposed to bring us complete happiness forever after, or to the fear, tragedy, and violence of the world at large, real or imagined.

The Unplug! practice centers on being mindful of what you take in. Most of us are conscious of what we eat and who we choose to spend time with, but how mindful are we of what we watch on television browse on the computer? What are we taking as we consume this compelling information? How does it feel when it “goes in?”

Reading for Pleasure, Nourishment (or for Work or School) is fine:

Just make a conscious choice this week. Is this “input” necessary? Is it going to be helpful and nourishing or distressing and activating?

To shift from sensory overload to sensory rest, we can begin to train our minds and bodies to turn inward for nourishment. Taking a media fast is a simple (although challenging) way to do this, as is spending some time each day in silence, and taking time out for a retreat in nature. This practice of a media fast will prepare and ripen the soil of your mind for our all-day retreat Enjoy!

Areas of Stress

Reflect on your own life…In which of these areas do you experience the most acute stress? How do you respond to that stress? Are there “patterns of response” or “maladaptive habits” that could be revised as you cultivate mindfulness?

Physical Pain / Discomfort

Emotional Distress

Persistent Thoughts or Worries

Time

Sleep

Intimate and Family Relationships

People and Social Interactions

Roles (at work, at home…)

Work

Food

The World

Money

Stuff (organizing and maintaining it)

_________________

Communication Lens 1: Passive, Aggressive, and Assertive

Passive Communication

When using passive communication, we do not express our needs or feelings effectively. Passive individuals often do not respond at all to hurtful situations, and instead allow themselves to be taken advantage of or treated unfairly. Passive communicators are often trying to avoid conflict and unpleasant situations, but the style is often self-defeating.

Traits of passive communication:

- Poor eye contact

- Allows others to infringe upon their rights

- Softly spoken and use of vague words (“I guess… Well….”)

- Allows others to take advantage

Aggressive Communication

When we engage in aggressive communication we often violate the rights of others when expressing our own feelings and needs. Aggressive individuals may be verbally abusive to further their own interests.

Traits of aggressive communication:

- Use of criticism, humiliation and domination

- Frequent interruptions and failure to listen to others

- Easily frustrated

- Speaking in a loud or overbearing manner

- Aggressive body language and intimidating use of eye contact

Assertive Communication

When we employ assertive communication, we express our needs and feelings in a way that also respects the rights of others. This mode of communication displays respect for each person involved in the exchange.

Traits of assertive communication:

- Listens without interrupting

- Clearly states needs and wants using “I” statements

- Warm eye contact

- Warm, expressive voice

Communication Lens 2: The Stoplight Model

from Susan Chapman, The Five Keys to Mindful Communication.

Mindfulness teacher Susan Chapman employs a simple but powerful model of the stoplight to help us understand our own state and be curious about the state of the other when attempting to communicate. Discerning our own state and the state of the other helps us to be more skillful in communication. Perhaps it just isn’t the right time to bring up this topic!

The Green Light: Openness

When we’re open, we don’t see our individual needs opposing the needs of others. We experience a “we-first” state of mind, because we appreciate that our personal survival depends on the well-being of our relationships. We express this connectedness to others through open communication patterns. Open communication tunes us in to whatever is going on in the present moment, whether comfortable or not. Openness is heartfelt, willing to share the joy and pain of others. Because we’re not blocked by our own opinions, our conversations with others explore new worlds of experience. We learn, change, and expand.

The Red Light: Defensive

When we’re closed and defensive, we feel emotionally hungry. We look to others to rescue us from aloneness. We might try to manipulate and control them to get what we need. Because these strategies never really work, we inevitably become disappointed with people. We suffer, and we cause others to suffer.

When we close down and become defensive—for a few minutes, a few days, a few months, or even a lifetime—we’re cutting ourselves off not only from others, but also from our natural ability to communicate. Mindful communication trains us to notice when we’ve stopped using our innate communication wisdom—the red light.

The Yellow Light: In-Between